Automating web scraping with GitHub Actions and R: an example from New Jersey

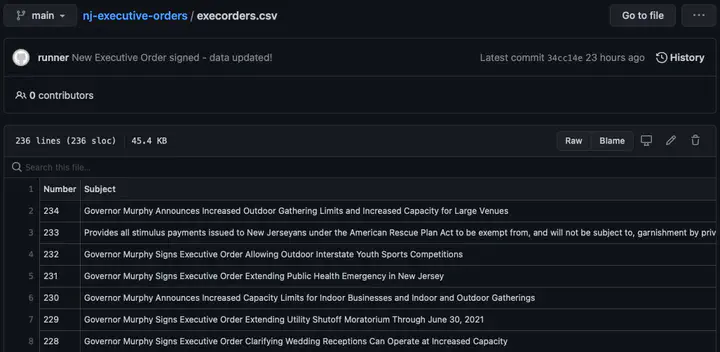

The end result of the action as seen on GitHub

The end result of the action as seen on GitHubGitHub Actions is a powerful tool for building code, running tests & other repetitive tasks related to software development. It’s also a powerful, if somewhat underutilized tool for deploying web scrapers written in R to the internet and automatically publishing a version-controlled copy of the scraped data using GitHub.

In this post, I’ll show how I used GitHub Actions to automate running a scraper written in R that checks to see if New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed a new executive order on a given day by scraping a table from a state website using {rvest} and commit an updated CSV file to a GitHub repository if there is new data obtained by the scraper and detected by Git.

I previously wrote about a quick sentiment analysis that I performed on the corpus of Governor Phil Murphy’s executive orders using the {syuzhet} package in R. What I didn’t cover in that post was the actual work of scraping the data prior to loading it into the underlying API that powers the TrentonTracker legislaitve analytics platform that is in development as part of a larger project.

I’m pretty keen on the power of automating data science and software development workflows using GitHub Actions, so I thought this scraper would be something that could be easily adapted to making use of the feature.

Actions are defined by a simple YAML file that lives in the .github/workflows directory in your repository. Here is the one I wrote for this project:

The workflow

on:

schedule:

- cron: '0 4 * * *'

push:

branches: main

name: Scrape Executive Orders

jobs:

render:

name: Scrape Executive Orders

runs-on: macOS-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- uses: r-lib/actions/setup-r@v1

- name: Install dependencies

run: Rscript -e 'install.packages(c("rvest","dplyr","lubridate"))'

- name: Scrape the data

run: Rscript scrape_exec_orders.R

- name: Commit results

run: |

git add -A

git commit -m 'New Executive Order signed - data updated!' || echo "No changes to commit"

git push origin || echo "No changes to commit"

This workflow defines a set of actions that will be run each time a change is pushed to the main branch of the repository and on a set schedule at midnight every day. First, it installs the needed dependencies on one of GitHub’s macOS-based systems, then it calls my R code that is hosted in the script scrape_exec_orders.R.

Each time that this R script is run, a CSV file with the latest version of data on the governor’s executive orders is produced and written to the current working directory and the status of the runs can be seen from the Actions tab in the GitHub repository.

Using the system-level Git command, the second step of the action is to determine if there were any new additions to the file since the previous commit. The action checks if there were changes to the CSV file storing the data, and if so it commits the updated file back to the GitHub repository. Then, the new data can be accessed via GitHub like any other file hosted on the service, making it suitable for integration in other data science and development workflows.

GitHub Actions is not the first platform to build out an easy to use CI platform. But its tight integration with one of the most popular software development platforms and ease of use makes it dead simple to integrate into existing projects, hence my interest in integrating it with my existing web scraper.

Critics of this approach to deploying web scrapers may argue that a similar level of automation could have been achieved by just setting up a cron job to run on a server and committing the results to the GitHub repository, but that introduces additional complexity and potential time sinks on maintaining the server hosting the scraper. Most Linux distributions ship with a woefully outdated version of R, so there’s some manual effort involved in adding the proper keys and repositories to install the latest version. Second, like all servers, regular maintenance is involved by way of updates and security and hardware failures and hacks are an ever-present threat.

Scheduling and running web scrapers for some of my projects via GitHub Actions is a better alternative in many respects because it avoids these pitfalls thanks to the ephemeral nature of the service’s compute function, not unlike other serverless and public cloud offerings.

For my use case of GitHub Actions, I have learned to appreciate that you can strive to have anything you want, but not everything. As I have balanced my side projects while working full-time in academia, I don’t have the hours of free time to devote to manually maintaining my creations like I did in the past.

That’s why it is against this background that I see a lot of value in automating repetitive workflows like this. After running OPRAmachine for just over 3 years now, I have grown accustomed to getting a barrage of emails, calls and texts when that platform goes offline or malfunctions for some reason.

The design of the OPRAmachine platform - a customized Ruby on Rails app running on top of Linux - necessitates that I spend manual time & effort on resolving issues like the ones described above. Automating the deployment of the scraper via GitHub Actions frees me of some of the potential pitfalls of having to maintain my own infrastructure; I won’t have to go troubleshoot a server or some arcane software issue because my server broke down for this.

The time I would have spent manually setting up a server to host and automate this scraper can now be spent on something else, since I can be reasonably confident that this approach to automation is more easily maintainable than others and less likely to break.